“The clearest way into the Universe is through a forest wilderness.”

– John Muir.

Some (if not most) of the monsters humanity envisages (youngsters and adults) tend to have some sort (or a lot) of animal in them. Why? (the Guru ponders…). Well, this lady believes that it is mainly because of what we have been historically and culturally fed with. By this I’m talking about myths, bedtime stories (yes, you know, the big bad wolf?), folklore.

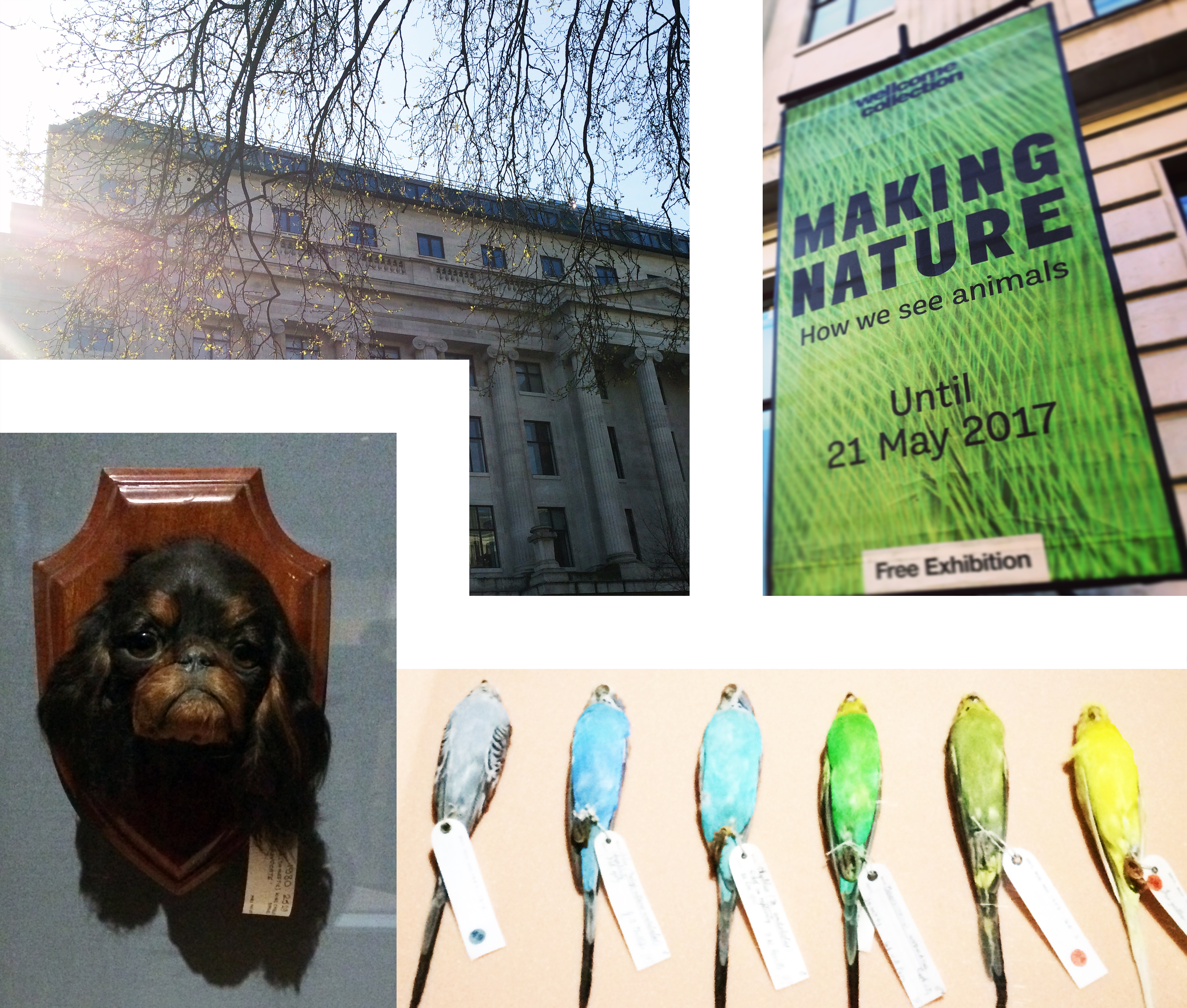

Animals come and go, have appeared and disappeared from the planet because of lack of adaptability or because of weakness or fragility. True, we don’t help with our excesses but it is also true that nature behaves in this merciless way. Yet, we try to save them, learn from them, protect them, and use them as we continue looking in them a reflection of ourselves. Our history with animals appears to be intertwined with our own fears, powers and weaknesses. And who has caused all this interweaving of perceptions? Us! And how are we going to sort it out? Well, that’s one of the questions that arises when visiting this extraordinary exhibition from the Wellcome Trust: Making Nature, How we see animals?

“It’s the zoo that’s been built not to look like animal’s natural habitat. It’s what vets learned from papier-mâché horse teeth. It’s whether you think the tiger looking in the mirror can see itself. It’s a perfect 3D-printed replica of a lion skull. No matter how you see nature now, you’ll never see it the same way again.” From Wellcome Trust: Making Nature, How we see animals? Leaflet.

(IT’S NOT WHAT YOU SEE. IT’S HOW YOU SEE IT).

I step in the imposing building of the Wellcome Trust in London and can’t contain the anticipation to get in this exhibition and see, if as they promised, they’ll change my mind and my perception of how I see nature (animals to be more precise).

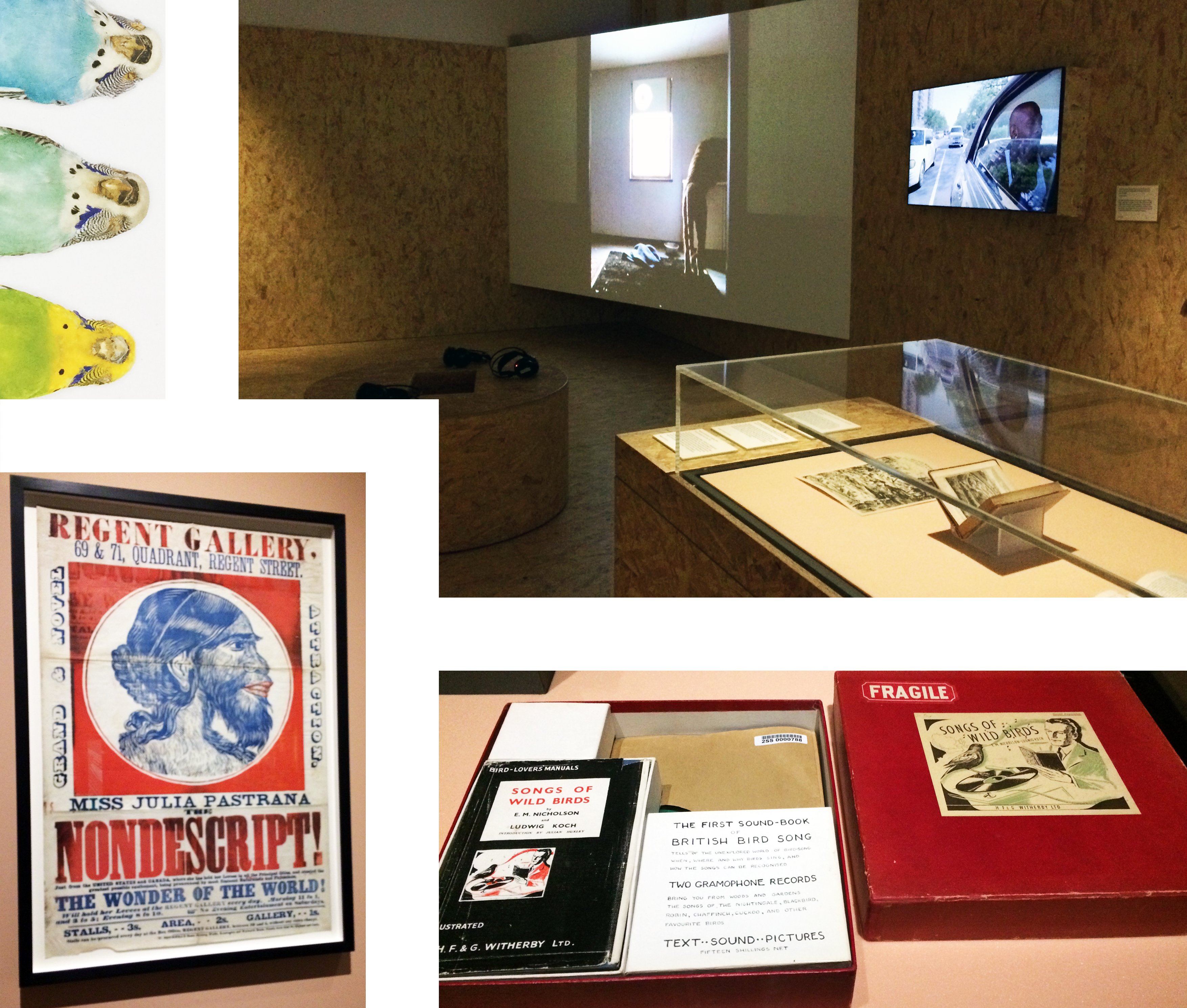

The exhibition describes in four words how we humans, through history and our intent to catalogue animals, have tried to solve the problem by approaching them in four different ways: ordering, displaying, observing and making.

Ordering them has been based on religion initially (providing mankind with the very special treatment and categorizing them as the “image of God”) and later still positioning them at the top of the pyramid by classifying them as Homo Sapiens (‘wise man”). We still carry this classification system, which affects the value we place on particular animals until today.

Displaying over the years has taken different arrangements. They echo scientific methods to sympathize with other species while documenting wider cultural attitudes too that shape, and are shaped by science. The depiction of certain animals in a prevalent culture often exaggerates the virtues and conducts expressed in museum displays, establishing themselves in modern mythology and creating typecasts that loiter in our collective cognizance.

Observing animals became an institution when zoos were created. Their records disclose how perceptions of nature developed and convey a contemporary propensity to sentimentalize life in the wild. They speak of how we create mascots and merchandising around the idea of human qualities. Story telling that burdens the animal with our very own hopes and fears.

The mention of the Center for PostNatural History explains how humans breed or genetically alter animals. This is a visual narrative of animals described by their cultural history, which at the same time recognises how they sustain human society.

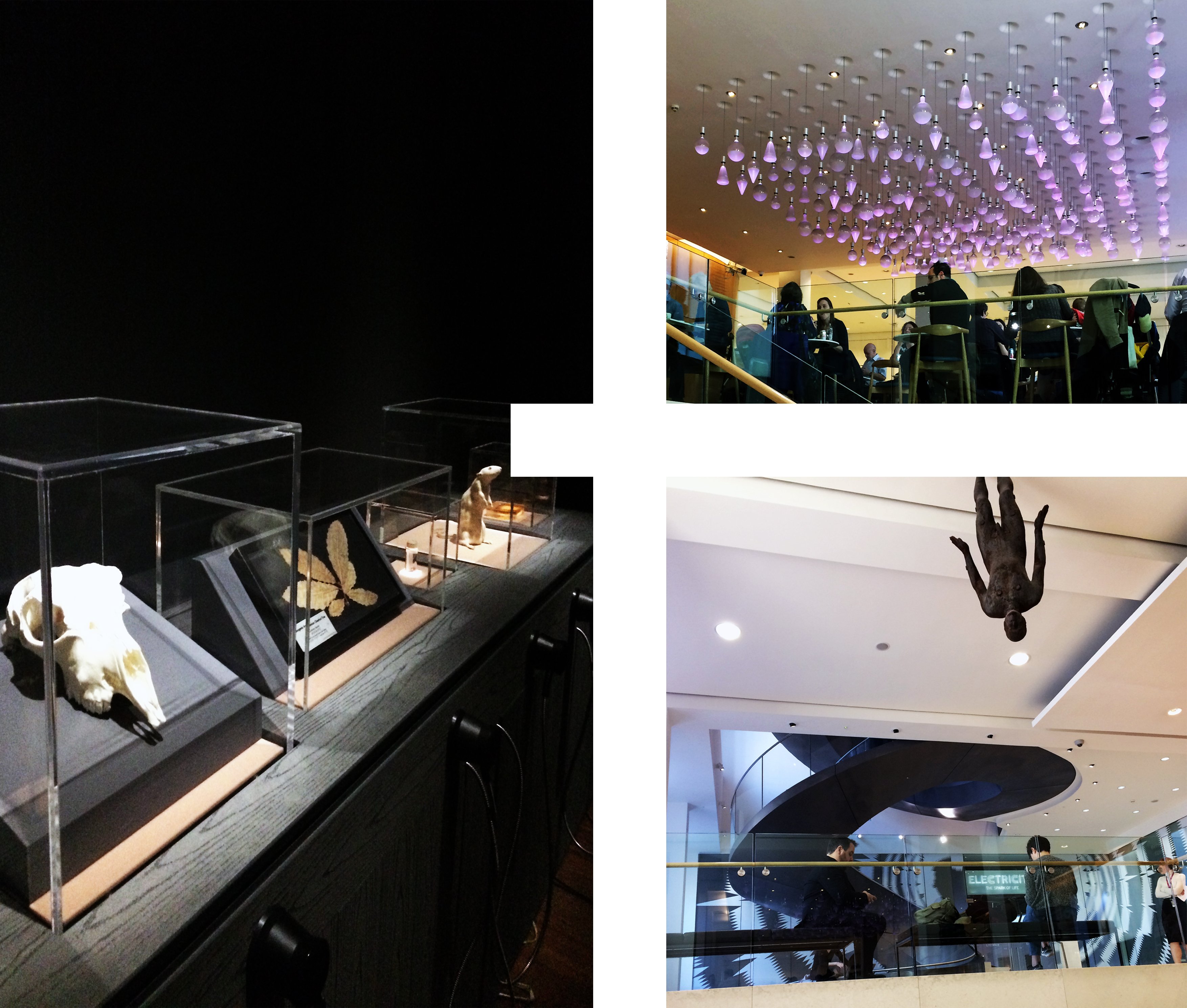

So, once I looked at this beautifully curated exhibition, watch extremely touching videos (the one of the Puerto Rican parrot was my favourite!) and had a very nice coffee in the lovely restaurant at the Wellcome Trust, I realised exactly how this exhibition changed my perspective of animals.

To work in the fur industry is not easy. The trade has been full of myths around it causing the people involved in it to give, quite frequently, a boring explanation of their daily labour to others. Useless to say that wouldn’t normally happen in any other activity. Questionability about the real necessity of fur, its source and methodology has justified people to come and ask you every day why you work with, like or use fur. The humanisation of some animals (in particular baby seals from the 40’s to the 60’s through the use of marketing and folklore such as Seal Island from Walt Disney) started a boom for activists to milk this notion of endearing looking animals being abused by the fur trade.

Our relationship with animals is like a bad marriage (yes people, the Guru has had a few). You believe that you found someone so similar to you, to whom you don’t even need to talk to because he/she just gets you. But, in the moment you move in and both sides start behaving as individuals (or in simple words: as what they really are), the struggle for understanding (and more importantly, respecting and admiring) begins. During this exhibition it took a while for me to have enough energy to stand up after watching Ming of Harlem: Twenty One Storeys in the Air: a video installation that explores the true story of Antoine Yates who lives in a flat with a tiger called Ming and a large alligator. Yates talks about his relationship with the animal and how he did what he did for “love” while you watch in a bigger screen a massive tiger, stuck in a flat and looking seriously puzzled… Just like a bad married wife not understanding why she’s stuck in a flat, waiting for “someone” to come (as he promised), feeling lost, betrayed, misunderstood and lonely. Oh dear! Where is all that “love” gone? Oh, I’m so sorry! Am I making this (until that day) unknown tiger the recipient of MY feelings and remembrances? Exactly my point! We just have to stop unfairly providing animals with our historical, personal and very human baggage.

This Guru believes that until we start concentrating more on applying regional laws and regulations and getting involved in programs to improve standards (eg Welfur, FCUSA Humane Care Certification Program, Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Mink) instead of treating animals like equals or stuffed toys, our relationship and perception of them will be far from fair. The fur industry lives and thrives because of animals and it would be cynical and wrong to believe we overuse or abuse them; it would be economically self-destructive. This is the reason why we stick to laws, rules and programs. Because this industry understands animals as historic companions that have generously provided us with food, protection, clothing and beauty, we owe them the duty to treat them with respect, sticking to the rules and providing them with what they need, and not with what we think they need.

P.S.The weather is lovely so this Guru won’t stop (except for a quick cup of coffee) and will take you next week to one of the trendiest installations in London. On her way, she will take you to one of the best-known brands in London. Get ready my darling readers, we are going downtown!

The Fur Guru

xx