Unlike the Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams exhibition – an exploration of one of couture’s greatest designers – as I navigate the Mary Quant exhibition also housed at the iconic Victoria and Albert museum (V&A), it becomes apparent that on display is a total rejection of Parisian couture and everything the fashion elite represented. Chronicling Quant’s twenty-year heyday and rebellion between 1955 and 1975, this exhibition showcases a crusade for teenage and young women’s social and sexual emancipation through fashion, re-defining the youth-led spirit of 1960’s and cementing London as the new fashion capital of the world. Over 120 garments, accessories, sketches, cosmetics and photographs envelope two floors of the V&A, showcasing Quant’s revolutionary designs of post-war London, an era defined as the beginning of what we today know as ‘street style’.

Born in 1930 in south-east London, Dame Mary Quant became Britain’s best-known designer and a powerful role model for working women in the latter half of the twentieth century. Quant was evacuated during the Second World War growing up in a period of austerity and clothes rationing. However, Quant’s love for design did not waiver, and while attending art school she met like-minded creative and free-thinking individuals who would inspire her to create. Quant’s first job was trimming high class hats at Erik’s, a couture milliner in Mayfair, but drawn to the pubs and cafes nestled on the buzzing Chelsea Kings Road, the location where Quant would open her first boutique, Quant sought to re-write the fashion rule-book.

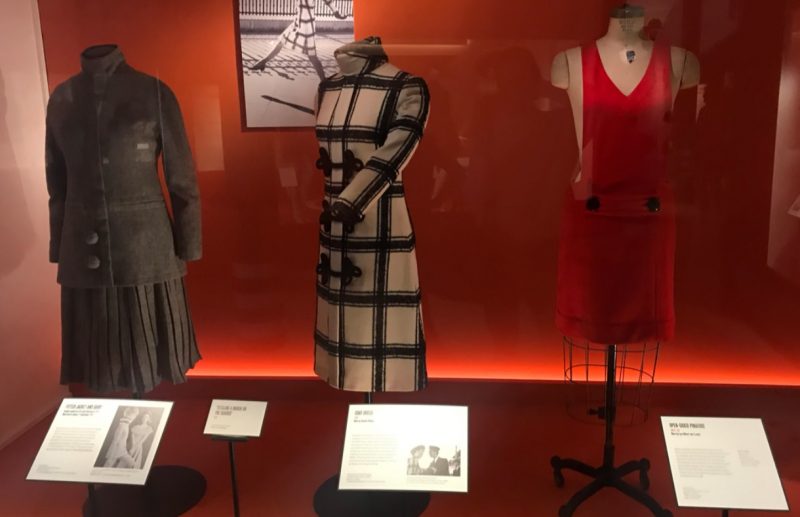

My journey through the exhibition begins with the story of Quant’s boutique, fittingly named ‘Bazaar’. A quote from Quant reads, “The whole point of fashion is to make fashionable clothes available to everyone,” while a glass case branded ‘The Birth of Boutique’ showcases some of Quants first designs as they would have been displayed in her shop window on Kings Road in Chelsea, London. One of the first designers to harness the power of the media to market her brand, Quant re-shaped post-war fashion which was heavily saturated with unattainable couture, and democratised it through mass manufacturing so every woman of any class could experiment with her style with Quants designs.

Upon Quant’s party opening for Bazaar, everything, including her pinafore pleats, blouses and party dresses, all sold out. But not stopping there, Quant used the money she made to buy fabrics from renowned department store Harrods every morning, creating new designs. And three-years after the opening of Bazaar, Quant opened her second boutique opposite Harrods, challenging the dominance of the fashion elite in that area. This brazen move by Quant coincided with the ‘Death of the Debutante’ movement. “Snobbery has gone out of fashion”, Quant contested, and she was right. Fashion Editors endorsed Bazaar with its fresh designs, unique window displays and alternative fashion shows. Quant was on her way to becoming fashions next big thing.

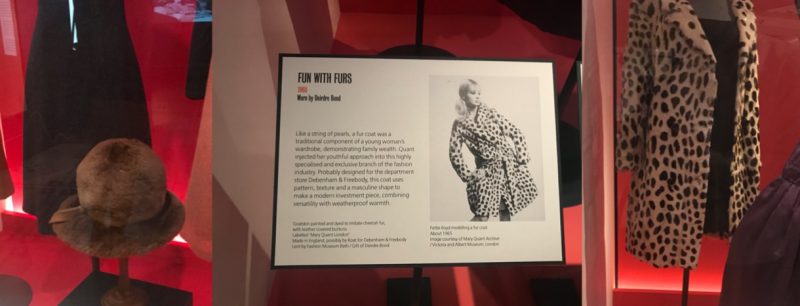

A lover of all materials, Quant designed with a range of textures and shapes. Only on material would provide her with such versatility – fur. Fur was a staple on the London high-street and fashion scene, therefore it comes as no surprise that illuminated by spotlights is the most magnificent leopard fur coat. Quant loved fur, often revitalising the material for the fashionista of the 60s and 70s. Quant’s furs, along with all of her designs, appeals to both ‘duchesses and typists’.

A plinth tucked under the show-stealing fur coat reads, “Like a string of pearls, a fur coat was a traditional component of a young woman’s wardrobe, demonstrating her family wealth.” A social signifier that is prevalent today. The plinth continues, “Quant injected her youthful approach into this highly specialised and exclusive branch of the fashion industry. Probably designed for the department store Debenham & Freebody, this coat used pattern, texture and a masculine shape to make a modern investment piece, combining versatility with weatherproof warmth.” This plinth summarises the unique advantages that fur – the craftsmanship and versatility – that no other material can rival. Fur, shearling and feathers were all specialities of Quant and her fun with furs and all natural materials certainly helped perpetuate its and her popularity.

As the exhibition continues to explore Quant’s career, I’m presented with her Ginger Group collection from 1963. A political term for a pressure group, the verb ginger was used to describe something which pepped things up. The name encompassed the collection which served Quant’s aim to produce playful, edgy clothing that everyone can enjoy. Building on her brand by working with the next generation of models, photographers and fashion editors, Quant’s commercial success continued to grow as part of the ‘Mod’ movement. It wasn’t long before women’s sexual liberation was infused with Quant’s pop art inspirations, and the miniskirt was created, changing fashion’s history forever.

For most people, when you say the name Mary Quant, they tend to conjure up images of miniskirts as this is a trend synonymous with Quant’s name and brand. And while the debate around who invented and who popularised the miniskirt has never been full-answered, with the French crediting André Courrèges for first daring to elevate hemlines thigh high, the shock factor helped perpetuate Quant’s brand into US markets. Therefore, it seems fitting that five mannequins towering over the staircase of this exhibition serve as a stark reminder of not only women freedom in fashion but their emancipation in the larger social context. For the first time, women could be who and what they wanted, and their fashions could reflect that.

Many more collections on display ignite my fashion flare. Taking inspiration for a wide array of sources, Quants ‘Subverting Menswear’ collection borrowed from the boys to create playful womenswear which delicately balanced masculine and feminine forms. This included trousers which were rarely seen on women outside of the home. And as I turn the corner I’m met by the glare of PVC, immediately intrigued, I rush over to the glass case which houses Quant’s ‘Wet collection” launched in 1963. A collection which would have the same appeal today as it did in the early 60s, I could truly envision this patent collection, with its water-tight stitching and matching hats, in a high-street shop window the collection.

Quant was at the epicentre of the ‘Youthquake’ era. Her fashion was bought to life by two of the world’s first supermodels Twiggy and Jean Shrimpton, and her creations made London the new fashion hub. This exhibition showcases Quant’s influence in fashion, but while the skirts maybe mini, her reach was mega. Quant gave women what they wanted, in return they gave her fame and success. The 1960s was a time of liberation and revolution in fashion, the landscape back then is almost unrecognisable from the one we live with today. Free from social constraint, women around the world enjoyed the new creations of a brazen Quant, from fur coats and hats, to wool pinafores and PVC rain macs, Quant was forward-thinking and unruly.